On April 2014 Cem Kaner and Rex Black had a debate on stage at STPCon Spring 2014 titled “Schools of Software Testing: Useful Paradigm or Negative Influence?” about the impact of the Schools of Software Testing such as Context Driven Testing.

For historical reference, the debate was transcribed:

The Introduction

Chairperson: Welcome to the STPCon Spring 2014 recordings.

We’re going to talk a little bit about the schools of testing, and I don’t know how many of you have been following the debates out there, but we thought it would be interesting to bring a couple of the gentlemen that have been at the heart of the debate to come here.

Have a conversation about their points of view to a little point, counterpoint, and then we’re going to have a little bit of audience participation as part of that. So I’m going to be out there when they kind of laid the foundation of their arguments and go back and forth and I’ll be close by. So if I have to wrestle them to the ground, I will. And I’m looking for a couple of the big guys that can help me out, because these guys could probably take me, but I’ll be out there with a microphone. So I think we’re gonna have a good time here enjoying this debate and interacting. We thought it would be a nice way to interact.

So I’m going to invite up onto the stage first, Rex Black. Rex, come on up. Give Rex a hand. He’s the president of RBCS. He’s got a popular book managing the testing process, has sold over 100,000 copies and he has 11 other books and he’s great all around guy. I sat through his risk based testing last week and his Agile Tester. He’s introducing the agile testing certification coming up. And he’s a great guy and really a great trainer.

I’d like to also welcome up to the stage Mr. Cem Kaner. Another great guy. He’s a J.D., Ph.D.,. He’s a professor of software engineering at Florida Institute of Technology. He’s the author also of several books, including Lessons Learned and Software Testing and the Domain Testing Workbook. He’s also a software test luminary award winner. And we appreciate that.

And I am going to hand over the stage to them. They’ve agreed on the rules of engagement. They are a little bit close for my comfort. Anybody watch the arm wrestling? I think there may be a little bit of that going back and forth. But they’ve agreed that Rex is going to open it up and then Cem is going to discuss and then they’re going to go back and forth and then we’ll engage you guys.

Take it away, Rex.

The Opening Pitch

Rex Black: OK, great. Thanks. So anybody know who Sun Tzu is? Sun Tzu is the great Chinese military strategist who wrote a somewhat famous book on military strategy, Art of War. And you might go, well, what does this guy have to do with software testing? Well, what it has to do with, is that my basic position here is that there are no schools of testing. That they don’t exist. That what actually exists are strategies. And that what we need to be as test professionals is like that guy. You know, there’s a saying up there he’s giving you advice on if you’re in this situation with respect to your enemy, then do this. But if you’re in this other situation with respect to your enemy, then do this. In other words, what you do depends on your situation. The strategy that you choose depends on your situation.

What’s wrong with the Concept of Schools?

So what’s wrong with this concept of schools? Well, I think if you look at the founding text here that Cem wrote with James Bach and Bret Pettichord, as you know, there’s some good stuff in it. There’s the seven principles of context driven testing at the end, which I think is for the most part, good stuff. I think a lot of it is common sense. But as Mark Twain said about common sense, the problem with common sense is it’s not always so common. So it doesn’t hurt to say things that need to be said, even if we should all know them.

But OK, so there’s some general good ideas there. But what about the actual results of this? What has context driven testing actually brought for us? Well, I would say for the most part, more heat than light and has not been an illuminating concept as a whole. So I have a number of complaints here. In the papers that you’ll find on the Internet, probably the most notable one would be Bret Pettichord’s paper on the schools of testing. There are three other schools besides context driven testing to find. And then later there was an addition made to that to add another one for agile testing.

You will, in my experience, not find anybody claiming membership in any of these other schools. So if this is such a useful way of organizing our thinking about how we do testing, how come nobody else is adopting it? The only people that talk about schools of testing are people who put themselves in the context driven school. Now, interestingly enough, if you say context driven. You notice that? The first slide? Sun Tzu, pretty context driven stuff there, right? If you’re in this situation, do this, if you’re in that situation, do that. So one would expect that that would be the kind of thing you would hear from people who are luminaries in context driven school.

Now, leaving aside Cem here, I think if you go out onto, say, Twitter and follow some of the folks who are self-proclaimed context driven testers and look at some of what they say on Twitter about testing, that’s going to be about the most prescriptive stuff that you find about testing on Twitter. Don’t ever do this. This is horrible. This doesn’t work. Categorical statements about what to do and what not to do. Which isn’t terribly context driven.

So it’s kind of an irony there is that the people who make pronouncements on Twitter that are the least context driven things you’re ever gonna find or tend to be mostly people who proclaim themselves as context driven. So perhaps they’re not very clear on the concept there. Now, prescriptive pronouncements are fine because prescriptive pronouncements can be the basis of a good debate.

Twitter Debates

And I’ve been through a few good debates on Twitter. Unfortunately, a lot of times what happens if you followed any of these debates on Twitter is that they aren’t actually good debates. They’ve devolved very quickly into shouting matches. And there is some amazingly rude stuff that gets thrown out there. Not particularly helpful. Okay. No, maybe it’s funny. It can be amusing. I suppose if you have a sense of humor, runs that kind of way. But are we really learning anything about how to do better testing and how to be better test professionals by trading character assassination and other kinds of insults on a public forum like Twitter? Or does it just make us look silly and unprofessional? All right. That would be my position. I’m all for a good debate. Happy to have one right here, right now. But I’ve got basic rules of it. You know, I’ve been around too long. I’m just too old to put up with a bunch of character assassination and rudeness if I want a deck kind of thing. I could teleport myself back into high school, I suppose, and relive that all over again.

But, you know, I also have two teenage daughters. So anytime I want that vicariously, I can always do this, you know, walk into the bedroom and just fill up a big cup of snark and, you know, off I go. I don’t need to go out on Twitter and get blasted with that stuff. And unfortunately, that’s that’s a lot of what it’s about. And as I said, this is more heat than light. Right. It’s not really illuminating things. Also I think another problem I have with it is that there is a feeling of orthodoxy about it. And this is just what I get, again, from listening to this stuff bounce around on Twitter, like, you know, the seven principles that I mentioned there at the top and found at the end of lessons learned software testing.

It’s really about Orthodoxy

It’s funny if you remember those seven principles and you go into a presentation by somebody who’s a self-proclaimed context driven test person, it all almost ought to be like a drinking game. You know, when they cite one of the principles and they’ll cite it literally. I’ve been in presentations like that. It’s almost like you should have to take a shot every time they say one of the principles verbatim, you know. So it’s orthodoxy. And so that bothers me, too, because we’re not at the point where we can have orthodoxies. We’re still at a point where we’re trying to figure out what this profession is all about and what we should be doing, what is good professional testing. And we don’t need orthodoxies for that. We need debate. My suggestion here is that we just set aside the whole idea of schools and say, no, there’s just a lot of different strategies and we should pick the appropriate strategy for the appropriate situation that we’re in and accept that different strategies work in different situations. And rather than demonize people whose preferred strategy is maybe different than our preferred strategy, that we engage again and move towards that type of engagement.

Interestingly enough, if you look back at 2000 or so when Lessons Learned in Software Testing were being written, those about 2000 and 2001. At that point in time, believe it or not, actually what has was relatively close professionally to a number of people who are now context driven testers and still I am close professionally to some of them, but others through this schism that’s been created would probably not have anything civilized to say about me. And I think that’s unfortunate. If we can get back to thinking about different strategies that we can choose and having a civilized debate that way, then I’m all for it. So that’s my opening pitch.

Schools of Thought

Cem Kaner: I arrived at university in 1970 during a period of huge social unrest. One of the pieces of unrest in terms of what I was studying involved a book published in 1962 about the structure of the scientific enterprise. He was writing mainly about the sciences, chemistry and physics. People talk today as if he was writing about the social sciences, but he was talking about the hard sciences and saying that everything about those fields was heavily influenced by the social dynamics of the field.

The organizing principles of the field that the structures of how they thought about things were heavily influenced by the interactions of groups of folks doing science. And their interactions really defined the ways that the field progressed. By 1970, this had become part of the mainstream of scientific discussion and I ran into it many times.

As an undergraduate, I studied mainly mathematics and philosophy. In philosophy, most of my courses were in Indian philosophy where I learned that appearances are enormously deceiving and what was left was primarily a study of Kant and Hegel, who talked very much about the progress and evolution of ideas in terms of a dynamic of opposition. You’d have folks who advocated for well organized views. The views would largely grind against each other for a while until finally a third way would evolve. And again, this notion that intellectual progress comes through the interaction of the people in the enterprise. It’s not a simple linear model which has been the traditional way of talking about science. It’s not an impersonal model like the notions of strategy. Strategies are there, but they’re performed and advocated by people.

Studying Schools of Thought

So schools of thought, as I studied them back then, were the hosts for this dialectic. They were the places that people who disagreed basically formed their views and espoused them and worked on what was going to become the next thing.

In 1974, I took a two semester course with Kurt Danziger on theories of human nature. Danziger eventually became famous for writing books on the social psychology of the history of science, reinterpreting much of how people did experimental psychology in terms of the social dynamics of the field rather than in terms of methodologies that the people now get taught were always accepted as the right way to do things. He walks through and traces how some of these things evolved. And you’re looking, you go, wow, that was really a human creation subject to an enormous amount of interpersonal debate. Reading, constructing the subject, preparing for this. I came to realize again how much my thinking owed to that 1974 course with Danziger. And the perspective that scientists engage in what they do through disagreements, through marketing of their ideas, through propaganda, through interpersonal conflicts.

They pay enormous amounts of attention to what work is fundable, what work is sellable. It’s remarkable looking inside the human realities of the business as it is, I think, in software testing. And then I went to graduate school. I went to a school that was famous for experimental psychology, McMaster University in Canada. We had several of the leading activists in several schools that were well-known and intensely competing.

It was a privilege. I could read about the conflicts between these guys in textbooks and then watch them face to face. Some of them in the school and others who would come and visit. One of the things that was very noticeable through the seven years that I was at McMaster was the collegiality of these folks there. There was an enormous amount of room to learn through disagreements, and there was a lot of civility in the disagreement that made it possible for us to learn. So coming from that background, it was really no surprise that I came to Silicon Valley, finally, in 1983, very well primed to notice the deep disagreements that existed then in the field.

The idea that the schism is new is hilarious to me. To notice the interpersonal fault lines that existed and to kind of keep track of them as they evolved and to notice segregations of groups of folks, as they advocated for their points of view.

Extreme Fragmentation

Now, Rex is grumpy about how he’s being treated by some colleagues that I think are a little too exuberant about something. This is not a new phenomenon. There’s a lot of writing when people talk about the social psychology of science, about this dimension that runs from stagnation on the one side where everybody pretends to agree and disagreement is suppressed out through fragmentation on the other side where nobody can talk to each other. And there’s this sense that progress happens somewhere in the middle.

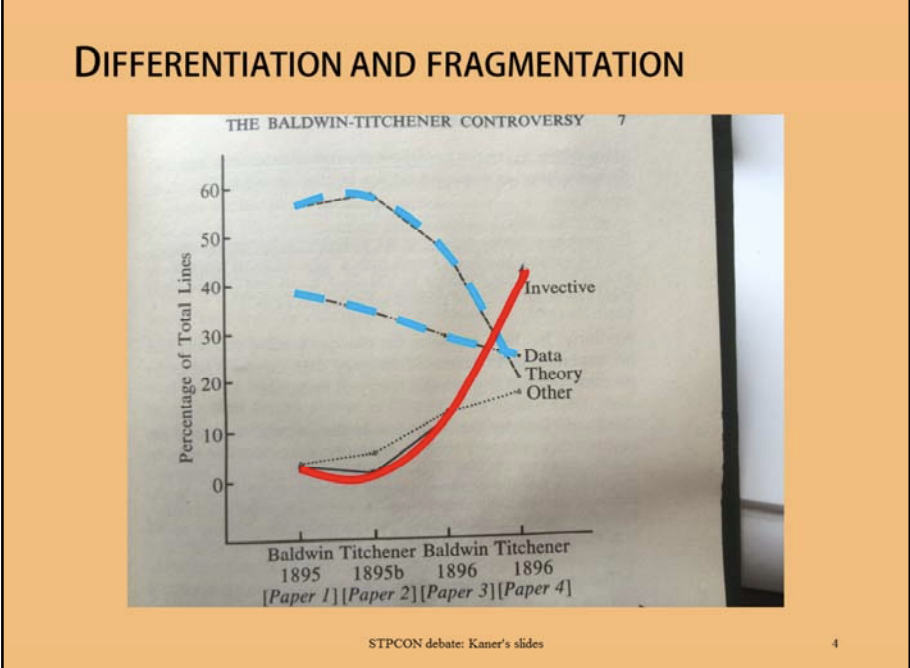

This is from Krantz’s book on the history of schools of psychology. It’s a wonderful slide. He takes a two year debate. This is fast, but it was relative to how these things go. But this was a famous clash between two schools.

And you see in 1895 that these guys started out talking theory and data. And by the end of 1896, they were screaming about each other’s mother. Seriously. There was no longer a space in that discussion for constructive engagement. And this is what we’re talking about when we’re talking about extreme fragmentation.

There’s certainly some of that going on and I find it just as annoying as Rex does because there’s no progress that comes from this. And the whole point to me of having discussed opposition is neither of these is right. There will always be a better next way, it would be nice to be able to take some steps toward finding it.

Disagreements in the Field

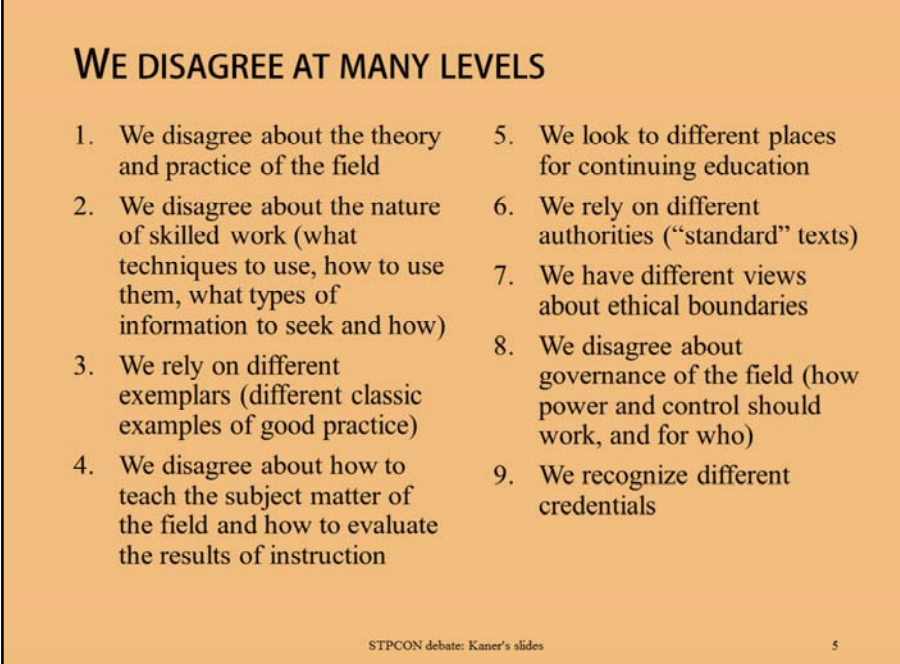

So I think in terms of points of view, there are disagreements in the field when I read books published by folks who are training for ISTQB, for example. And when I read the IEEE standards, I see many kinds of disagreements between my views and the views of many people I think of as having similar views and and other folks.

They are basic disagreements:

- We have disagreements about what’s good practice.

- We have disagreements about what a credential means.

- We have fundamental disagreements about what the nature of effective instruction is.

- How do you teach this stuff?

- What are the best examples?

These are deep disagreements. That doesn’t mean you have to be nasty to each other about them. I’ve seen several other cases in other fields where people have disagreements every bit as deep and much more long lasting, but they can talk about them. But we have. And we’ve had them for a long time.

The Standards Process

The process for resolving disagreements that I ran into in 1984 was pretty simple. I could try to join in IEEE Standards Committee as I did in 1984 and was told to go away. Could you not bother me? Throughout the standards process, which I got involved in or tried to get involved in for the next 15 years, what I learned was that nothing I would ever say would have enough political power behind it to make any significant difference in anything that I worked on. People were going to espouse what I think of as a traditional way of doing testing and tell me that I’m an isolated person who has a strange point of view.

Now, that strange point of view these days is called agile. And as that group, which I think of is a school has evolved, cohered, protested, read this stuff in 1999, 2000, 2001. They had an influence together that none of us could have alone. So as you have folks, Capers Jones, several times, talks about how no one will adopt metrics. Very few companies have organized metrics, programs. And then he talks about people engaging in malpractice for not doing measurement the way that he approves. I look at it a different way from my consulting and experience. I met executive after executive who’d engaged in these measurement programs, found out how much measurement dysfunction had been caused and said we’re never going to do something like that again. We’re going to have to have a better rationale for imposing that cost on the organization.

- The one way to deal with that is to listen to the failures and try to adapt.

- Another way is to try to create standards that legislate to become an expert witness who says if they don’t do this, then they’re negligent.

To force on a field the things that it won’t naturally do. Many of the standards that I see take things that are not widely done and say these are the best practices that must be done. Generally, they’re not done for good reason. And imposing is the last resort of people who don’t have anything better to offer. You can say that anyone who opposes those is schismatic. But again, this has been a set of opposition since the early 1970s. It just keeps playing out. So the standards process, for example, is very heavily politicized as somebody interested in the social psychology of science, scientists like sure. And it is in physics, too. Welcome to progress in intellectual fields. But because it’s heavily politicized, you’re dealing with people or the underlying causes of this, you’re dealing with people who have things to gain from standards.

Large contracting organizations have interest in having standards that forward their way of doing business. And individuals and small groups who operate in different ways aren’t necessarily well enough funded to get into the same process and have the same kind of voice. You end up with standards writing process that perpetuates. I think the interests of a few groups. Now, you might disagree with my political analysis. The notion that there is a political analysis to go through for these kinds of things. Anytime you have power and control in a field, you have a political analysis to do what conclusions you draw are different, but you have a political analysis to do.

We have an interesting piece through the 1990s. Certainly you have this continuum between unification and fragmentation. In the standards world you had unification. People publicly, you go to the start of the conference, people are saying the same thing, not necessarily meaning the same thing but mouthing the same words. In practice, watching what was going on in California, the practices in the attitudes were widely diverse. And the question that I had was how do I find a voice to talk about the many different approaches that I’m actually seeing as I’m going from company to company and conference to conference. How do we get folks to recognize that when they’re speaking, they’re often talking past each other. They’re not hearing what they’re talking about. How do I give them a framework so that they can, to some better degree, interpret what they’re hearing instead of just having it go by and they learn nothing from it?

I came up with a variety of ideas for how to characterize differences. Initially, I started talking about paradigms. Kuhn, in the structure of scientific revolutions, used paradigms in what’s been counted as 35 different ways. And so everything that I said turned into something that was fundamentally ambiguous. I eventually gave up on that term. Kuhn wrote later that he thought he should give up on that term, too.

Ultimately, during the lessons learning process, we decided that we would characterize what we saw in terms of the concept of schools of thought. You can use different words, communities of practice, scientific, social networks. There’s lots of terminology that’s used. This is pretty widely studied across many fields and it’s commonplace in certainly all social sciences. And I think of software testing as a social science, but in all social sciences, it’s commonplace. They have groups of a few hundred to a few thousand folks who espouse a very different viewpoint, analyze things in very different ways from other folks in strategic management at the moment. There are twelve identified schools and tremendous amounts of debate among those. Are they going to stabilize at 12? I doubt it. There are fundamental issues they haven’t figured out yet and people are trying to figure out how to make progress on that.

I’m going to stop. There’s other stuff that I can say later. Go for it.

Rhetorical Terrorism

Rex Black: OK. Thanks, Cem. Interesting stuff there. So listening to you, I made a few notes you mentioned that I was grumpy about the way that it was being addressed. Now I’m actually over that. I was irritated at the point where people were making sport of trying to see who could strip the most meat off of my back on Twitter. Then I discovered this wonderful feature called Blocking. And now I’m just not. I just don’t you know, I don’t have a problem anymore. But but my concern with it is that, that kind of rhetoric, that kind of rhetorical terrorism, if you will, it shuts down the debate. Right. Because I think most people will eventually get to where I am with it, which is I’m not having anything to do with this crap. I’ve got better things to do with my life and my emotional energy than have shouting matches on Twitter.

Claims on ISTQB

So some other things that I wanted to point out to you. I noticed in going through your notes that you had citations for Spillner and Hambling books on ISTQB. I really, I mean, no offense to those fellows, but I mean, I think if you look at the authors of those books, they’re actually not the major authors of the ISTQB syllabi and so forth. So to say that those books adequately capture what the ISTQB program the certification is about, I think they’re not as authoritative as it might appear.

And I think if you read some of the other books, you’d find that there actually is disagreement within the ISTQB community. For example, you mentioned standards and there certainly are some people within the ISTQB community that are big on standards. Personally, I think that standards are a potentially useful source of interesting ideas sometimes. But the few times I’ve seen anybody trying to actually adhere to, say IEEE 829. My advice to them as a consultant has been, please stop doing that because that’s not working for you. That’s wasting your time. You’re over documenting. So I think it’s not so much that you mentioned an emphasis on specifications in the ISTQB program. It’s not so much an emphasis on specifications as an emphasis on test oracles, which I know is something that gets talked about a lot amongst people who declare themselves to be context driven.

Agile – Cleverly Marketed

We could have a lot of interesting discussions about test oracles if we weren’t so busy shouting at each other. Right. But the shouting, the shouting precludes the interesting conversations. And, you know, you mentioned Agile, too, which I think is interesting because Agile was very cleverly marketed. You mentioned marketing, certainly some very clever marketing of it, and interestingly enough, in a lot of cases that marketing was pushed by the very same companies, training providers, consultancies that were making money out of ISTQB training. And of course, one of the things that pushed Agile being successful as well was a certified scrum master and the associated certification programs. So, you know, if you’re saying you’ve got an issue with certification, well, then it’s sort of seems like you’d have an issue with Agile as well, because Agile has been pushed forward very much by certification.

Tower of Babel

Then the last point. Not the world’s most organized notes here. You mentioned schools as being commonplace. And OK, I can accept that you know a whole lot more about this study of schools and different professions than I do. All I know is the study of what it’s doing here in our profession.

And I would say that right now it’s not working. It’s not moving us forward. And so that gets back to the point that I made on my first slide of the trees. Judged by its fruit. Right. The fruit of this concept right now is, to my mind, bringing us less forward advancement and clarity and more personal conflict. And we’re definitely off into that fragmentation. I notice this is an interesting example here. Tower of Babel problem. Just recently, it became very popular for some advocates of context driven testing to talk about checking, which is always sort of an implicit sneer of checking versus testing. We’re not really testing. You’re checking. Basically, what they’ve done is just redefined two very common terms that go way back.

Verification and validation is saying that if you’re verifying against specifications, that’s just checking and that’s not important versus if you’re validating that the system actually does what a user customer stakeholder needs it to do, then that’s real testing. To me, there’s a place for both of those things and to come up with a snarky term to direct somebody who dares to actually test against requirements. What heresy. That’s not that’s not helpful. I mean, I think we need to recognize that there are times when you do have written requirements and or user stories or whatever we want to call them, and we should be testing against that. So that’s just an example of what I mean in terms of it’s not moving us forward in some cases is moving us backward or it’s just moving us around in a circle, which, you know, is OK, if you like, married or not.

So back over to you, sir.

Different Sets of Principles

Cem Kaner: Some of the things that Rex is citing from my slides, I handed Rex a draft of the slides a couple of days ago. And the full set is, I think, available. There are 44 slides, more than you’re possibly going to see in the debate. It’s interesting with agile watching what some of us would characterize as the progression of the Borg. For those of you who remember Star Trek, the Borg is an empire that basically assimilates everyone. And I get to read blog posts these days from folks who say, I want my agile back. This is a common quote theme. The version of Scrum that I’m seeing often practiced now looks a heck of a lot like test than code, which I associate with Bill Hetzel and David Galperin back in the 1980s in the testing community. It doesn’t feel very agile to me.

When I compare that to the very edgy, extreme programming movement of the turn of the century, it’s just a very different approach. It’s a different set of principles. There are certainly a bunch of folks who came out of that tradition who are still hanging on to it. Rightly or wrongly, and feel as though what they’re looking at, it’s marketed as agile today is a watering down the same way that total quality management was watered down. That became group hugs and quality circles and started out as very intense, humanistic statistical quality control things, as they get popular, get watered down and they get clever.

Marketing people find ways to drive divisions to sell their approach. And that’s part of the challenge of fragmentation. Look at me. I’m special in the United States of the 1990s and 2000s, polarization is a great seller. Political parties do it very well and they’ve modeled that for the rest of the country to follow. And several folks in several fields are following it. I hate it. There is a difference between division and schism. And I have no disagreement with you when you say that some of the people, especially on Twitter, which is kind of the host for every shallow, you know, here’s one hundred and forty word jab.

Even people who are thoughtful off with Twitter seem to think they have permission to be jerks on Twitter. And there’s a lot of it. And it’s unpleasant. It’s not helpful. It isn’t moving anybody forward except, I think, for some pocketbooks. But look, past those folks, and I think what you’re finding is that many people are thinking critically doesn’t necessarily mean destructively. Critically means what am I looking at? What’s the basis for this? What’s the reasoning here? Who thinks this is a good idea and why? Who thinks this is a bad idea and why? What other ideas are out there? Who advocates for those ideas? Why do they think theirs are better?

In the 80s and 90s, people told me that that kind of analysis basically didn’t exist. That you either thought in a fairly standard way or you’re off the map. The resistance that came when I tried to publish the first edition of testing computer software all the way through the publication of the book and finally getting my rights back from McGraw-Hill, the resistance through every piece of that process as I used Tabu words like exploratory testing was remarkable. I was an isolated individual. And I kept meeting other isolated individuals who thought similar ways.

It as astonishing that folks weren’t until they started gathering together and saying, look, this is what we collectively seem to believe. There is that horrible curve as you go to an extreme and you have to hit it and go, well, you know, you hit bottom, you bounce back. There is that horrible curve in. Some folks are getting it. But as we bounced back from that, where many people I think are today, there’s a lot of insightful, critical thinking about how different people approach problems that I don’t see any other way than this to have. Despite the costs that we’re seeing and I get to be a target of some of that, too. Despite the costs that we’re seeing in places like Twitter and on blogs, it’s annoying. It’s a price. But the notion of creating a forum for a free flow of critical discussion. I don’t see a good alternative.

Debates

Rex Black: I would tend to agree that there are some people out there that are doing exactly what you mentioned. So Ben Simo comes to mind of a guy who is able to put forward interesting ideas, debate them at the same time, be very respectful. And he obviously is doing exactly that. But I would say, though, that there is I think if you look at a lot of prescriptive pronouncements, which are the opposite of critical thinking to say under all circumstances, you should do this. And it happens under the color of people who are self-proclaimed context driven testers. And it said and then nobody from this same self-proclaimed school goes back and corrects it.

So that’s a frustration that I have, it says it seems to me that part of critical thinking is if there are people that are in agreement about something, that they will tend to sort of police each other. I know we certainly do that within the ISTQB School, if you want to call it that. We have very vigorous debates and arguments about things. And if you were in some of those working group meetings, you have like wow, that’s a pretty, pretty healthy debate there. And there are such disagreements. You know, I don’t see any evidence of that happening within the context driven community of people having debates back and forth criticizing each other’s ideas.

Public Corrections

Cem Kaner: There certainly have been such debates, some of them have been extremely acrimonious, and just as the debates that are internal to ISTQB don’t get very visible outside, some of the debates that you haven’t seen existed. Anyway in terms of public correcting, I think there have been a lot of public corrections but the challenge with Twitter is, and generally the challenge with marketing, if somebody has a business model of being polarizing then coming back to that person and saying, excuse me, you’re being needlessly polarizing. It sounds great, but you have to say it 4000 times.

Every time they’re needlessly polarizing, at a certain point you say, OK, they’ve got the message, they don’t like me anymore. They’re not going to change how they speak. I think I’ll ignore them. And I think that several of us are looking at the extreme of a fragmented discussion and saying, that’s farther than I’m interested in going. I’ve told people that now I need to get back to work because ultimately they are going around in circles. Let’s all talk only about the basics of the field and not about the development of new techniques or new skills or the deepening of skills.

Every time we talk about the latest bad definition, we distract ourselves from moving forward and at some point you have to do the real work in the field. The other stuff is entertainment and marketing. So I think that there are many of us who said time to get back to work. This stuff is a distraction. It doesn’t mean that we can avoid doing what I think of is very critical thinking about the social dynamics. But we don’t have to do it in obnoxious ways.

Rex Black: I abide that.

Question and Answer

Cem Kaner: Maybe it’s time for questions.

Rex Black: I think so.

Scott (Audience): So it almost sounds like you two guys at the end of the accord discussions, slash debate came back to almost some level of agreement. My thought in question here is whether or not we calm schools and those kinds of things is kind of almost irrelevant to me whether that’s a strategy or a genre. I see those kinds of distinctions coming out of most fields, both of science and music and art and literature. Whether or not the participants are aware that they’re in a particular genre of music sometimes isn’t that important is what the outside world sees as country music or rock and roll. Then there’s a few people that cross back and forth between genres and or schools and try and influence all of them. So for me, it’s what do we do to make things move forward and progress? I, by the way, think Twitter is a terrible medium for any kind of true discussion debate. I mean, 140 characters, you know, any complex idea doesn’t fit in there. And so where do we take the debate and critical thought discussion? How do we critique the thoughts that are out there? I think, you know, the other fields like psychology mentioned, I forget the name of the university. People came there from both sides and discussed in a proper forum. Aside from conferences like this, do we have those forums in our industry or do we need more of them?

Chairperson: Whichever one wants to start first, you want to know? Sure.

Rex Black: I guess it responds to your opening statement. I think there are things that Cem and I agree on. I remain convinced until results prove otherwise that on the whole this concept of schools of testing, whether that was something that actually existed or not. But the whole concept and the way that the concept has played out in practice in our profession has been a net negative. I don’t blame Cem for that. I’m not saying shame on you for introducing the concept as obviously you threw it out there and you couldn’t have predicted. OK. This is exactly what’s going on. Well, I assume you can, but if you could predict those kinds of things, you’d probably be doing stock trading, I would guess, and a whole lot richer than any of us in this role. If you can predict how a random idea thrown out into the public is going to turn out, that’s quite a prediction. But I remain convinced that on the whole, it’s been a negative influence so far. And that would be we would be far better off if we spent our time trying to think collectively about what are the different strategies that are out there, which ones work under what circumstances. What are the enablers? What are the risks? What are the disabled or is associated with the different strategies?

And that kind of changing the discussion to that and that sort of discussion, I think would have a way of depersonalizing it. As I think you mentioned, that the strategies are a depersonalized thing. So I still would prefer that we talk about strategies and move away from schools.

Chairperson: Cem, Do you want to add?

Cem Kaner: Sure, you made a point about how there are people in the middle between schools. And that’s a point that I want to follow up on as an empirical thing. One of the ways that people in Specialty Library Sciences study the formation and continuation of schools is through something called code citation analysis. They look at who somebody reads and whose work they talk about, and they notice that there are clusters of people who primarily pay attention to each other and turn into a feedback loop for each other. And then there are other clusters who primarily pay attention to their group. And when there’s talk between these, it’s often critical. Then you find folks who sit in places where they write papers that take from each of the groups and they try to tie them together. Those folks often carry a lot of ideas and practices from one group to another. They’re often at the forefront of change in the groups. They’re often the carriers of the new synthesis.

But the people who are sitting on the edge of one group or unaffiliated, I know in the Twitter stream, there’s a constant statement. You have to be in one of the four schools. It’s ridiculous. And empirically, it’s an unjustifiable generalization. It doesn’t work that way. The notion, though, that you get some folks who finally get insight from increasingly well-developed points of view that are polished by people comparing them and come up and say this is another proposal that might work better than either of these is, I think, how a lot of things that I’ve seen evolve, evolve.

University Environment

I think the university environment fosters a lot of the kind of debate and discussion that you’re wishing could happen. And one of the reasons why I left an industrial practice to go back to university is that it’s a better home for that kind of thing. I have collegial, sometimes quite firm discussions with people who I very, very firmly disagree with on a daily basis. And sometimes those turned into a pretty deep theoretical debates. And when I’m not doing it, our students are doing it. But we can do that. Publish together, work together. I go to parties together and learn from each other together. There is some amount of that that I’m able to get in professional practice as well. We founded the lost workshops, peer workshops, partially with the goal of creating forums where that kind of deeper discussion that compares views could happen and there are still some forums of that kind that go. Rex during that period whose somebody who very much walked back and forth across different schools. So he came to meetings on heuristic and exploratory test techniques and felt at home there, just as I’m sure you were at meetings on my standards development and feeling justice home. The notion that Rex is a person must be pinned to a specific named school or any person in this room must be pinned to a specific name school, I think it’s ludicrous. But the notions that you can be a contributor to that were heavily influenced by that, I think is empirical. Watch what the person says and what they do, who they hang out with and which ideas they echo back. And you learn something about their perspective.

Context Dependent – Religion of Standards

Chairperson: We have another question over here and not I know Twitter has is getting a bad rap here. But if we could keep the answers to like a Twitter bite of about a minute so that we can get a few more questions, that would be great.

Audience: Cem, I appreciate listening to you this morning, because up until half an hour ago, I had no idea why this context dependent school was telling me that I was full of crap. I feel like I’m one who straddles the schools I hated in the 90s when clowns told me that I had to do these best practices when clearly they were not best practices for the context that I was in. But nowadays I have the context, people telling me I’m full of crap because maybe sometimes I think we ought to have written test cases or maybe sometimes we want to automate in a certain way. Is there any way to keep these schools from becoming religions? Because that’s what I see happening. That you’ve got the religion of context dependent, the religion of standards, etc.

Cem Kaner: Rex commented that I couldn’t have known what I was suggesting, that we name a school, that we’d have the fragmenting impact that we had. That fragmentation is a normal situation. Go back a few hundred years, you’ll see the same dynamic. Go to any other field today and you’ll see some point in their history where they had the same dynamic. It’s a pendulum and swings. It has swung to an annoying place. We don’t all have to play on that swing. We can choose to refuse to accept that a few extreme people’s pronouncements define that point of view and talk instead about what we think instead of what they want to tell us that we should pay them to tell us to think.

Rex Black: I think unfortunately, Cem, what we are seeing is that that pendulum swing is by no means done but is actually accelerating. So an example of that was that ISTQB wanted to participate as a sponsor, give money to the Association for Software Testing. Their conference and had done that in the past. But current leadership of the AST, so the allegedly the vanguard of the context driven school got together and said, nope, you can’t be here.

Cem Kaner: Is that again where this was a couple of years ago?

Rex Black: No. This is this year that this happened. There was an issue a few years ago where my own company got told that we couldn’t sponsor because we had annoyed James Bache by existing, by breathing. I wasn’t even breathing there. I wasn’t even actually physically there. I just annoyed him by giving money to ASD. So I think we see this continue to accelerate and there’s no end in sight to what Jamie is talking about at this point to me.

Future Testing Thoughts

Audience: I think from a historical point of view, it’s very interesting about the schools. But what I’m interested really in is your point of view each individually about the future of testing. Testing can be very frustrating for and something wonderful for us practitioners. But how do we make it such that we are more successful more of the time and make it easier so we all can go home and sleep on the weekends at our houses and take vacations and so forth. So what are your thoughts on the future of testing?

Cem Kaner: I think we’re dealing with a few different classes of problems. One of the classes of problems is, especially in Europe and Asia, there are stunningly many people who were told that to get a job in the field, they had to get certified. They took courses that they didn’t respect. They parroted things back on the exams that they didn’t believe. They resented it and they’re now getting folks who say you were ripped off. You should be angry and that is part of the marketing that’s being done in the name of context driven testing and that wave of anger. Not everybody who takes those certifications feels that way, but if you’re forced to do anything. You’re probably more ready to be irritated about it than not. And there are a lot of people who are irritated and those folks are gonna be suckers for the extremist point of view. They’re emotionally ready for it and that’s gonna be part of the future of this field. And I’m sorry, but ISTQB is part of that problem.

Rex Black: Well, I think if you look at surveys that the ISTQB and ASTQB have done, the overwhelming majority of people that have gone through the program or used the program in their companies are very satisfied with it. I’m certainly not to say that it’s perfect that we have everything figured out, but we are very much trying to stay in tune with the audience and with our stakeholders. If there are companies out there that are misusing the certification in some way, we can’t stop that, right? I mean, this it’s the same as you. I can’t hold you responsible for some lame brain on Twitter making an obnoxious ass out of himself because you wrote seven principles of context driven testing at the end of a book, right? We at the ISTQB and ASTQB can’t take responsibility for what everybody does with the syllabus, but we do try to course correct. Now, in terms of where the future is going, I don’t think the ISTQB is trying to find the future or trying to support it. I mean, where I see things going is towards an actual form of engineering, larger form of software engineering and testing existing within that. I have to look at other fields of engineering and how they got to where they are and how far away we are from that and I think we’re in for a very interesting hundred years before we’re at the point where people are routinely sleeping in their beds on weekends and not working long hours and so forth. You know, so I think eventually we’ll get there. Eventually it gets like civil engineering where you know, it’s just not all that exciting typically to build a bridge when the upside of that is you get to sleep at home in your bed at night. The downside of that is that the basic laws of physics and civil engineering are all figured out and so you don’t get to be one of the people who figured them out and one of the exciting things about those of us in this realm is for we get to be part of how the profession gets defined. We get to be part of how that’s all figured out and we can either have fun and get along while we’re doing that or we can to quote the brilliant mind of Steve Martin “throw dog poop on each other’s shoes”.

Categorization of Schools of Testing

Chairperson: Here’s another question.

Audience: Hi there. First, sorry, I went to thank both of you for speaking on this topic and although you guys are getting dangerously close into the certification versus not certification debate. So I want to be careful that because I could take another couple of hours. What I want to ask though, is, you know, categorization is inherently divisive and the schools of thought provided a way to categorize ideas, practices, principles, etc. And personally, I find that kind of dichotomies are useful because those ideas, concepts and principles typically have related benefits and pitfalls. So Rex, earlier you were speaking about you haven’t seen much useful fruit come from the categorization of the schools of testing. I think that they do and that they help categorize these ideas, these correlated benefits and pitfalls. And I think that is tremendously beneficial to the industry because actually it enables you to do what your point was earlier, which is pick from the strategies that are best for the context in which you’re operating, right? If you’re from an academic environment or manufacturing or whatever, you’re going to have different things that are important to you. So I find that’s at least a benefit at doing the categorization, I kind of want to get your thoughts on that and as well as yours, Cem. Thanks.

Rex Black: So I’m not by any means opposed to categorizing things, you know. And I think categorizing the different testing strategies is very useful because by categorizing, you can start to say these are enablers, disablers, risks and opportunities associated with each strategy. And that can lead us to make smarter choices about picking the right strategy in the right situation. My problem with the schools is that it’s become more about identifying oneself as a person with a school as opposed to identifying situations in which certain practices are likely to work better or worse. And I think that way of looking at it is gonna be a lot more helpful to us because again, as Cem said, it does depersonalized things. And I think that allows us to step back from some of the emotional energy that’s gotten all boiled up over the last 10 or 15 years on this and get into what works and why and what situations and studying that and sharing ideas that way.

Cem Kaner: So I think that the notion of strategic thinking is useful. And I think that there is a tremendous amount more attention paid to the analysis of techniques. Where does it work? Where does it not work? Why does it work? Why does it not work? Who does it work for and under what circumstances? I think that the discussion is much more prevalent presence in the testing community today than it was 15 years ago. And personally, I take some credit for that. I think that we created a discussion that was very, very hard to have 20 years ago and in my personal experience actively discouraged. But I want to come back in terms of the future to a different piece. There is the political future of the profession and I think we’re on an interesting ride for many years to come. And then there’s the technical future of the profession.

Personally, I’m working on how to train people more deeply in specific test techniques. How do we actually get better at things? One of the core differences that I see between testing and programing is that there is an enormous amount of support for skill development of programmers all through university and practitioner training, getting better at programing, getting to be a master of programing in terms of a master individual contributor who does these things really well. We don’t have much of that in this field. We need to develop more of it. That’s where I’m spending most of my time. It’s not a school related issue, but it’s a fundamental for any kind of progress of the overriding views. Similarly, with test automation, now that computers have gotten very fast, we can do numbers of tests that were inconceivable years ago. Years ago, Doug Hoffman ran a test with four billion test series with 4 billion automated tests on a supercomputer. People were amazed that it took him 6 minutes. And when I used to teach a course where I said, how long will this take? People talked about years to do that. We replicated that on a cheap little Lenovo computer that we got for 250 bucks at Office Depot. It took 8 minutes, 2 minutes longer than the supercomputer several years ago. There are things that we can, as a practical matter, do today in automation that were inconceivable before. There are optimizations based on how expensive it is to run tests that are obsolete with current equipment. That means we have an opportunity for a different vision of test automation and we need to work on that. Part of that is political. But there are a lot of traditions which are the political parts. But much of that is technical.

LAWST Inspired Testing

Chairperson: We have time for one more question. That’s going to be Dan here.

Dan (Audience): Hi, Cem and Rex. This is Dan Downing. I was introduced in the hallway earlier as the guru of performance testing, but I really reject that label. I’m just another tester who has been around performance testing and has learned a few things in my tiny contexts. But I’m glad to hear that we didn’t need boxing gloves on your face this morning that really you guys are in violent agreement. Refreshing to see that. I’ve been around some of these strong personalities that were named and unnamed in today’s debate about schools and context driven testing. I found them to be intelligent and have creative ideas, obnoxious and rude. So many of the adjectives that both of you have danced around here in your characterizations. And I’d like to suggest to Mike Cooper’s question about so what is the future of testing is that instead of debating schools and paradigms and fisticuffs and 140 character soundbites, which I totally ignore or block as both of you have mentioned, that we instead take a page from your LAWST inspired. For those of you who don’t know who LAWST is, Los Altos Workshop On Software Testing, I believe, Cem, that you were instrumental in introducing a few years back a page from that manifesto, if that’s what we can call it, which is to instead I tell stories about our individual experiences doing a recent testing project. I would have loved to have heard Cem, one of your recent Silicon Valley experiences where something worked or didn’t work. Rex, one of your recent consulting gigs where that may have worked, because I think I would have gained a lot more in the understanding of that specific context and in the specifics of how you applied, whatever principles or approaches that happened to have worked in that particular situation. So I love the notion that the best way to learn is from somebody else’s story is told in first person with all of the color specifics and limitations of a single engagement. So I would like to come to the next STPcon and hear you talk about that instead of the debate.

Chairperson: You have Twitter time to answer.

Rex Black: So I would just say to or to react to that. I mean, if you want to hear me telling war stories, I do free webinars every month. They go on for 90 minutes and there’s a bunch of Q and A at the end after the 60 minute presentation, so feel free. Happy to do those and I tend to agree in general that, you know, sharing anecdotes about things that work and things that don’t work in specific situations is very useful, particularly in an environment where people were listening to those anecdotes and accepting, yes this actually happened and yes, this is meaningful. And what can I learn from it?

Cem Kaner: LAWST are inherently small group meetings because they also allow for detailed questioning of the speaker, which occasionally turns into discovery that the speaker didn’t really have the experience or not the one that he’s describing. Rebecca Fiedler and I still host the workshop on teaching software testing, which is a LAWST meeting every January in Florida. And Doug Hoffman, I believe, is organizing the next Los Altos workshop on software testing, I think LAWST19, to focus on test oracles probably sometime in the fall. I I still think they’re a fantastic way for sharing knowledge. But the problem is that bigger than 15 in a room destroys the meeting. So I don’t know how to do it here.

Closing Comments

Chairperson: I know we could go on all day talking about this, but we have a lot of sessions out there to get to. But I want to thank Cem and Rex. Will you give them a hand?

Thank you for listening to this STPCon Spring 2014 session recording. We hope you can join us for the next STPCon because on this November 3rd through 6th in Denver, Colorado. Learn more at softwaretestpro.com/stpconf14.

Pingback: Testing Bits: 402 – July 18th – July 24th, 2021 | Testing Curator Blog